The telecom crowd favors three- and four-letter acronyms. You know them, I’m sure: GSM, LTE, LAN, GPS, PBX, UMTS, CDMA, VoIP… and the list goes on. We’ve loved them since the first arrival of Flip Wilson’s WYSIWYG. These and many others have become household terms, or at least they’ve been fully adopted into our business lexicon. Let’s sidestep the dispute over the actual (dis)advantages of this cryptic telecom jargon. Instead let’s focus on two specific “all caps” standards: SHAKEN, and STIR.

SHAKEN (Signature-based Handling of Asserted information using toKENs) and STIR (Secure Telephony Identity Revisited) is a suite of protocols and procedures intended to combat caller ID spoofing on public telephone networks. Feel free to skip ahead directly to the “implementation” section if you’re already familiar with STIR/SHAKEN. A brief primer is up next. (Though we encourage you to read on either way – we promise to keep you entertained!)

Robocallers, the Amish, and Digital Seppuku

As Jacob Nielsen puts it: “In the attention economy, anyone trying to connect with an audience must treat the user’s time as the ultimate resource.” Our telephone number is the last remaining frontier between our good old pre-digital personal identity and modern “infinity pools”. These include our Google account, Apple ID, Twitter, Instagram, Slack, Facebook, all those various messengers, and many, many (oh gosh, way too many) others.

We might decide to “quit Facebook,” promise ourselves “never” to restore Twitter’s 2FA, or even deactivate our personal Gmail. That last one – a full digital seppuku – is tough, and it risks making you look like you’re Amish. (And that, in fact, is what makes it even more valuable to try. 😉)

Trusted Calling Scenarios

But even if you have done all of this at some point, you’ve likely never really considered permanently throwing away your “main” SIM card – unless your mobile carrier really pissed you off. In the old days, a phone call from a known (or at least explainably unknown) number usually originated from one of a few familiar scenarios:

- The guy from your local pizza delivery (which still doesn’t have mobile ordering) has arrived with your Four Cheese special. Buzz him in immediately.

- Mom is calling, of course in the middle of an important Zoom conference. Nevertheless, her habit of calling at the wrong moment makes you feel a burst of affection. Quickly answer, and tell her you love her and you’ll call her back in a half hour.

- Add your own – we know you have them.

Undoubtedly, everything that makes us “confident” in something (whether that’s your favorite dish soap or your personal sense of spirituality) will eventually end up in the hands of unscrupulous entrepreneurs. The same happened with caller ID. The Chicago Tribune reported what might be the first major phone fraud case back in 1888. 1888! That’s less than two decades after the first telephone was even introduced by Alexander Graham Bell and what would later become AT&T.

There’s no need to explain what a robocall is. By now you know, and you probably keep your phone on silent because of them. And it’s not even just random outside marketers doing it now. When you get an automated reminder call from your cable provider come billing time, that’s a robocall too. It’s possible you consented to receiving these (remember that microscopic text in your cable subscription agreement?). The problem is, in most cases a customer has never consented to getting such calls.

“Pierre Poutine”: a Geeky Issue Turns Political 🇨🇦

Since the 1980s there have been various regulatory efforts to combat unsolicited calls. In 1991, US Congress passed the Telephone Consumer Protection Act. It introduced various safeguards, including the National Do Not Call Registry (which the robocallers never actually cared about). Regulatory frameworks for robocalls have risen up from time to time since then in many countries. Typically it occurrs whenever some savvy politician wants to capitalize on the grievances of ordinary folks while appearing “modern” and techy at the same time.

Things started looking serious in 2011, when robocalls became part of a voter suppression campaign during the Canadian federal election. A staffer from the country’s Conservative party was officially indicted, and the whole story sparked nationwide protests. Still, the situation repeated itself during another Canadian election in 2019.

IETF and RFC 4474

Well, we hinted that there’d be more scary initialisms to come, and you knew there would be. The real solution (as usual) came from the engineers. A long time ago, back in 2002, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), a San Francisco-based non-profit that develops and promotes voluntary Internet standards, created the Secure Telephony Identity Revisited (STIR) working group. STIR started developing a standard that relied on cryptographic tools to make secure and reliable call authentication. In 2006, after four years of drafting, STIR produced RFC 4474. The document defines a mechanism for securely identifying originators of SIP messages.

As Jon Peterson, one of the co-authors of RFC 4474, explains: “RFC 4474 did not see any practical implementation.” This dead-end happened for two reasons. First, there were no recognized certification authorities for telephone numbers. Therefore, the practical application of RFC 4474 limited itself to email-like IDs such as alice@example.com. The other reason is that the authors of RFC 4474 overdid it on the cryptography part. That made RFC 4474 so strict and “reliable” that it caused false negatives, making completely legitimate calls look suspicious.

In 2013, STIR decided to “revisit” the secure telephone identity. In part it happened because the rapid development of SIP telephony had made caller ID certification easier on behalf of the originating provider. This time, “frivals” of IETF joined as well. The Washington, DC-based Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions (ATIS) might have decided: “It’s enough for the US West Coast to rule the world of caller ID standardization.”

What Does This Have to Do with Bond, James Bond?

If you’ve ever watched a James Bond movie (and even if you haven’t, though that would be pretty amazing, with 27 of them out there since 1962) you might recall the fact that Mr. Bond likes his vodka martini “shaken, not stirred.” In case you don’t — here’s a quick memory refresher:

It turns out that the SHAKEN protocol got its name exactly because of its “not stirred” part. As Jim McEachern, a senior technology consultant with ATIS explained in an interview with the LA Times: “STIR already existed. So we knew we had to call the new system SHAKEN. We tortured the English language until we came up with an acronym.” Finally, the US East Coast could take its acronym revenge.

How is SHAKEN Better?

Besides being a landmark example of brilliant linguistic trolling in telecom, SHAKEN also contains a number of substantial technology improvements over STIR’s RFC 4474. And the major one is… (you knew it, right?) POTS. They call this a “retronym” and it stands for Plain Old Telephone Service. Not what you might have thought. The communication within POTS occurs over SS7 (Signaling System No. 7… aha! A James Bond allusion again?).

Before SHAKEN, the caller ID stored within the call’s SIP header was lost when the call was transferred via the SS7 network. This is a big deal, because the fraudulent party could now use the SIP > SS7 > SIP gateway for “traffic laundering.” Communication providers must accept SS7 traffic because the system is still operational (despite being introduced in 1975) and recognized by the ICU. This left STIR with a loophole, one that SHAKEN amends.

Remedies… or Why It’s Bad to Have the Spam Earmark if You’re a Small Telco

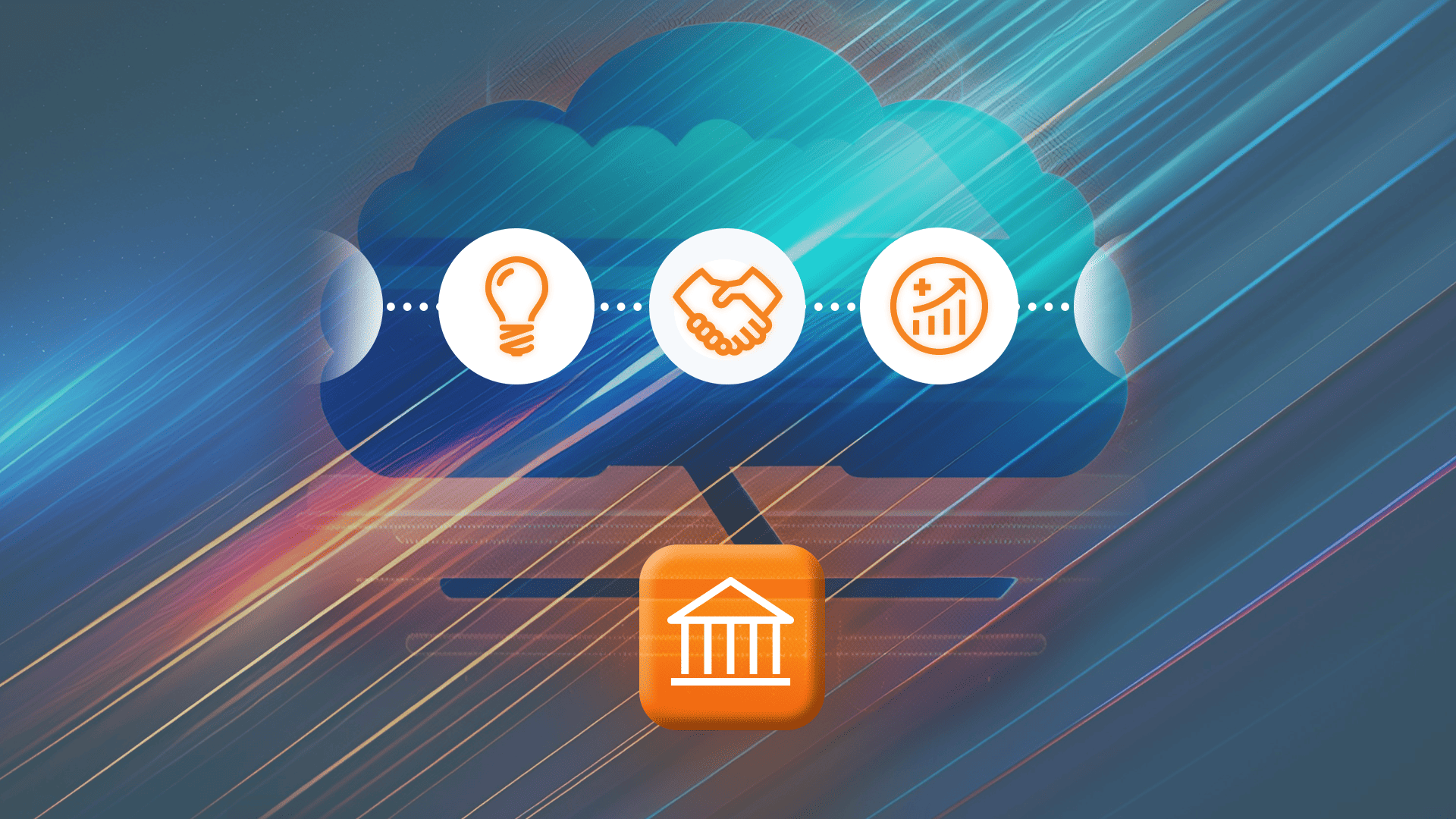

The TRACED Act (another acronym!), signed into US law at the end of 2019, the Canadian CRTC Decision 2019-402, and other local regulatory frameworks in various countries will definitely make life harder for robocallers – and for Telcos that facilitate robocalls. But the more imminent remedies actually come from the industry-wide adoption of the STIR/SHAKEN family of standards, not from the regulators’ wrath.

After a full-scale implementation of STIR/SHAKEN, all unattested traffic will get “suspicious” mark. This solution is flexible. It lets you, as the customer, make the ultimate decision about whether or not to take a call, but simultaneously it makes this decision well informed. And vice versa, too: STIR/SHAKEN will punish not only the non-compliant Telcos, but also their customers as well (by marking them as “suspicious callers” and degrading their attestation).

It’s All About the Rating

So if a Telco doesn’t implement STIR/SHAKEN, all calls by their subscribers will most likely get rejected by the other party. Most of us are already familiar with that feeling from years of watching our important emails end up in the recipient’s spam folder. (Guaranteed.)

Nobody wants to be marked a “spammer” or to be C-rated. In a world that enables (and encourages) instant carrier switching, this means loss of business to those Telcos who fail to implement STIR/SHAKEN after it becomes mainstream.

PortaOne, “Override Identity,” and How We Implemented STIR/SHAKEN Before It Was Cool

While STIR/SHAKEN is a great benefit to all end phone users and to the voice-calls ecosystem in general, implementing it is quite a pain for Telcos. This is particularly true for small and midsized companies. In other words: market players whose IT budgets have already suffered a lot from the recent OTT-spurred telecom recession. US Telcos have to implement call authentication by June 30, 2021. Canada imposed a harsher deadline: September 30, 2020 (hello again, Mr. Poutine).

So what should you do? Luckily, if you are or plan on becoming a PortaSwitch customer, not that much! You just need to connect PortaSwitch to the authorization/verification service of your choice. Just like our Mr. Bond, your PortaSwitch system comes STIR/SHAKEN ready beginning with MR89. There’s an “Override Identity” setting within our Customer Care Staff Interface (look for page 31).

“Override Identity” helps our customers make sure the P-Asserted Identity you get (and then pass to the next CSP) corresponds to the actual subscriber telephone number. This will help your TRACED compliance (or compliance with the analogous regulatory framework of your jurisdiction), among other things.

Here’s the trick: some customers “improve” their SIP call setup to alternate the caller ID. This is not necessarily for illegitimate reasons. It could be an outcome of an incorrect PBX system configuration on the end customer’s side, for example. Or, it could be something like when a retail chain subcontracts a customer care services agency to contact customers on their behalf, and there is a valid services agreement in place.

Why P-Asserted-ID Verification Does Matter for STIR/SHAKEN?

Why does our “Override ID” feature help? Before TRACED, Telcos did not necessarily enforce P-Asserted-ID verification within their network. Now, they have a handy tool to do so.

We’re still working on caller ID attestation/verification and ways to automate it. But we’re not alone – this is an industry-wide issue. Hopefully, it will be resolved soon. In the meantime, please get in touch with us to share your experience with implementing STIR/SHAKEN for your business. Have you encountered challenges while implementing it? Are there specific opportunities you see or want? We’re happy to listen, and happy to help.