Knowing your history helps you find and answer questions about your future. In this chapter of the PortaOne corporate saga, “the Prague Five”, we sought to answer the question of how our business came to be. In a sense, this is about the lives of our five founders: their coming-of-age and how their experiences and values shaped PortaOne today. You’ll hear personal stories from these founders on their road to building a thriving telecommunications vendor.

So, what do the cities of Riga, Prague, Vancouver, and Barcelona have to do with our corporate history? How did our chief designer produce his first creations on IBM System 360 and a roll of toilet paper? How did Bata shoes help our CEO start his career at Telenor? What makes PortaOne similar to Amazon? And finally, how did our founders work from home and create a truly distributed team back in 2001 – long before anyone could imagine what would happen in 2020/21?

This is a story of immigrants who refused to accept the rough and brutal post-Soviet reality, with its lack of human dignity and, for some, a disrespect for their individual gifts and talents. And it’s a story of emigrants who returned back home, helping their native countries become a part of a modern, united Europe and bringing opportunity to the younger generation by building a business that has a presence on every continent. (At least, that is, if you count the vessels using Inmarsat terminals in the Antarctic.)

Poet and civil rights activist Maya Angelou once wrote: “The more you know of your history, the more liberated you are.” We hope the research we did to write this story will someday help the next generation of PortaOne leadership better understand our future and innovate and lead this business forward in all the new directions. And, who knows? Perhaps some of those leaders were born in the very same year that PortaOne was established.

From a “Wonder Gadget” Maker to a Serial Entrepreneur

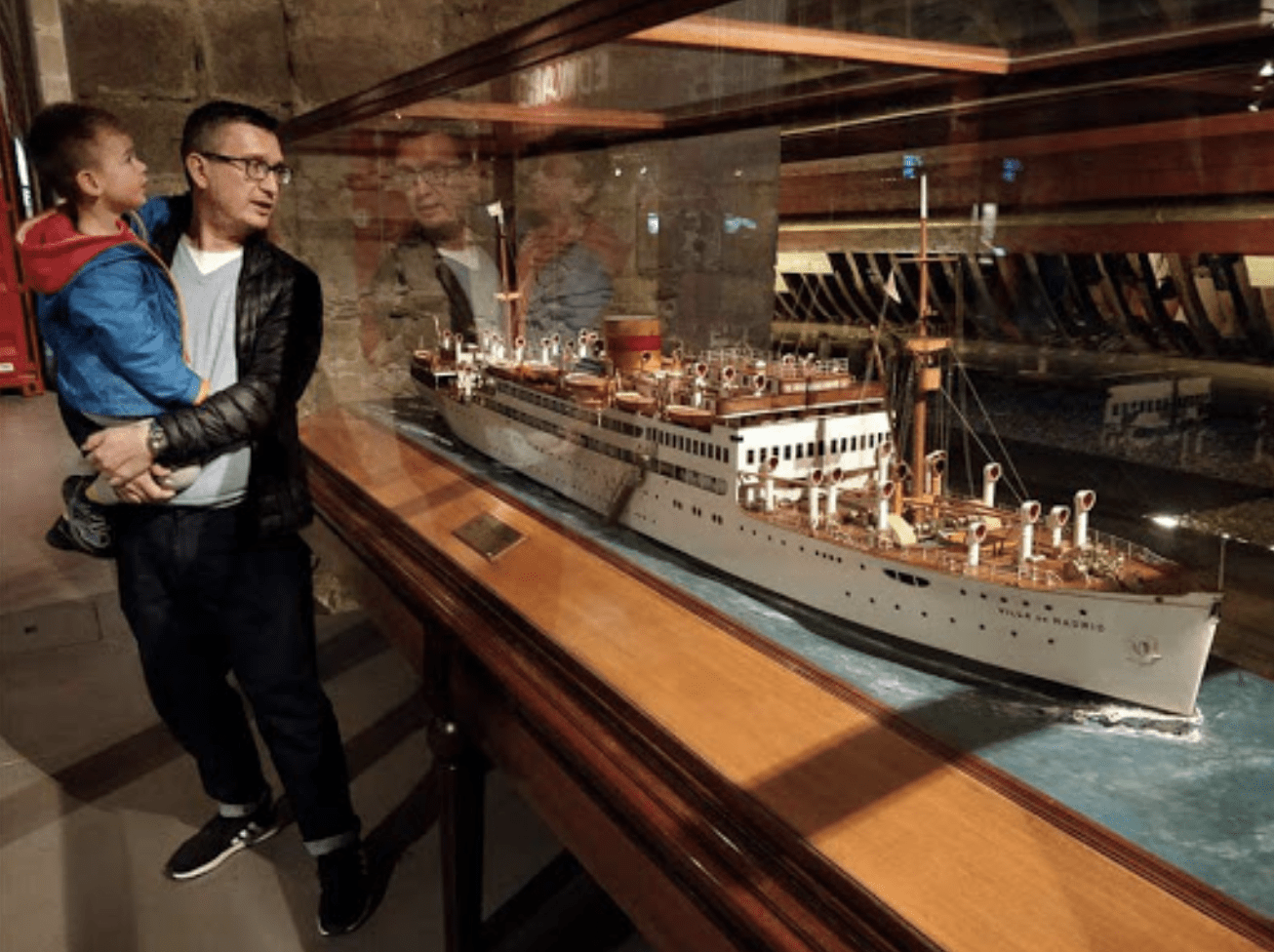

Oleksandr Kapitanenko (“Captain” to close friends and family) started his career in telecommunications in 1992, while he was a systems engineering student at Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute. That was his first business venture, and he went on to launch many more.

Telecommunications equipment was among the key symbols of Perestroika and the New Era for Eastern Europe. AON (Soviet naming for a calling party number determination accessory device) was the major telecom artifact of that time, besides imported South Korean fax machines and bulky Nokia or Ericsson mobile terminals working in NMT bandwidth. Because of the peculiarities of Soviet landline telecom protocols, these AONs were region-specific and could not be imported from abroad. That’s one reason why AONs are probably the most shamefully forgotten symbol of that era.

A Graduation Paper That Matured into a Modding Business

The machines built by Captain had a unique competitive advantage. “We were building the [AON] machines at home. We didn’t even have a brand. Just a ‘red box’ inside a gray Latvian phone. Testing assembled AONs required a Central Office Exchange simulator. We designed one together with Kostyantyn Deribin and described it in our joint university graduation paper in 1992,” he recalls during a video chat from his Vancouver house in January 2021.

The Fair Advantage

After articles appeared explaining AON technology, many radio engineers across the recently collapsed USSR rushed to build these machines. But the publicly available gadget designs and software solutions had a substantial shortcoming. For various reasons, they didn’t discover some caller IDs, killing the whole idea of “always knowing who’s calling.”

Some of these “undiscovered call” instances could have been corrected via debugging. In turn, that would require discovering and repeating a “problematic” call numerous times. This was difficult and sometimes impossible. But Captain’s simulation of a Central Office Exchange created a unique testing environment allowing unlimited debugging. This required far less time and effort. The result: his machines discovered more numbers, and so surpassed most of the competition.

AONs as a Post-Soviet Cultural Phenomenon

Still, why was “always knowing who’s calling” such a big deal during and immediately after the Perestroika era? Any fears over missing an important call should have been solved by the answering machine.

But while many people in Eastern Europe bought a landline phone with a digital answering machine in the late 1990s, very few liked “talking” to one. (Many answering machine owners would listen to their messages only to hear a faithfully recorded string of curse words and then a click as the caller hung up.) Keep in mind that, unlike in the US or “Rich” Europe, the Eastern European banking system didn’t develop enough for loan collectors to exist until the mid-2000s. And yes, those people love leaving voicemails, even in Ukraine.

AON’s Product/Market Fit

The pain AONs did help to solve was “answering the wrong call.” For example, the ones placed by a mother-in-law, a boss, an undesired admirer, a mobster offering to “protect” your business, or a KGB officer (or whatever local brand name this organization used after the Soviet collapse). Freedom was in the air. And people were enjoying the precious liberty to “ignore things” after over 70 years of not being able to do so.

Still, an answering machine – or an Internet-based voicemail, to be precise (10 years before Apple’s Visual Voicemail and 12 before Google Voice) – had its role to play in our story. And that means it’s time to introduce our next hero.

ES1035, Godzadva, the Phantom Lord, and the Terminal Bar

Things were tough for young Alexandre (now Saša) Starovoitov in the early 1990s. After a fight with some komsomolets (a member of the Soviet youth club, not the sunken nuclear submarine still leaking radiation into the Barents Sea), he was forced out of the Moscow Power Engineering Institute. In 1987, Saša ended up working as a technician for the Zhytomyr oblast branch of Ukrtelecom. He operated an ES1035 machine, a Soviet clone of IBM System/360.

The Toilet Printer

“The paper outages started occurring in the late 1980s. However, we still had to send out telephone bills to people in the entire region,” Saša recalls. So the employees of Zhytomyr Ukrtelecom came up with ingenious innovation. “We got rolls of toilet paper and inserted carpenter’s nails inside the printer’s drum. Sometimes the paper tore and the printer got stuck. Still, most of the time it worked and people got their bills on time.”

Saša was not a favorite with the grey-suited guys from “perviy otdel” – a secretive unit in each regional telecom branch, affiliated with KGB and responsible for law, order, and wiretapping. So they were happy to see him rejoin the ranks of academia. This time it was… Right, you guessed it – Kyiv Poly. “Me and Captain – we were destined to meet each other. I loved and played rock music, while he had the best sound recording equipment in the entire institute,” says Saša.

Let’s Rock!

Most of the Kyiv rockers around that time played and had their fun at an on-campus club called Barvy. Saša played various instruments with the “God za dva” band. The name derives from the “one year counts as two” policy for extremely hard working conditions (e.g. Northern Siberia or Artics). The band played an art rock, as we would call it today.

Thanks to rock music, Saša traveled to Prague in 1994 as a stand-in bass player with the hard rock group the Phantom Lord (not to be confused with the Metallica song, which undoubtedly inspired this group’s name). “We simply got on a bus and went to Prague,” he says. “They then left, while I stayed.”

“Vacation. How does that work?”

Living in Prague required some occupation besides playing rock music. Saša remembered his outstanding printing experience with Ukrtelecom and became a freelance print designer. That required a good computer. So, in December 1996, Saša traveled back to Kyiv to buy a computer from Captain (and to attend a New Year’s Party while he was there). The AONs were out of trend by that time, so Kapitanenko had switched to a PC assembly business.

“We met,” Saša recalls. “I bought a computer and asked if he planned on having a vacation.” Saša suggested spending some time in his favorite bar in Prague. Kapitanenko replied by asking how vacation works. Saša told Captain to pack his backpack, and off they went to Prague. After several weeks, Captain returned to Ukraine to sell his business and collect his family while Saša found them an apartment in Prague.

The Internet Voicemail

In Prague, Captain started researching the market for new opportunities. And he found one in the answering machines. “Czechia was more and more like Western Europe back then. People valued useful contacts, opportunities, and other people’s time,” he recalls. He created a combination of a personal IVR and an answering machine. The voice messages got converted into MP3 files, which could then be stored.

About the same time, Internet connection speed became sufficient to transfer low-fidelity MP3 files. So, he thought, what if we add a feature to listen to your voicemails online? The idea of a digital voicemail wasn’t a total novelty. Gordon Matthews filed for a digital voicemail US patent back in 1979. But VoIP, and what would later become the Session Initiation Protocol in 1999, delivered totally new opportunities and made the whole process more affordable.

The Terminal Bar and Telenor

The duo were frequent patrons of the Terminal Bar on Soukenická Street in the very center of Prague. The place was a combination of an Internet cafe, bookstore, and bar, with the office of the actual Terminal ISP located upstairs. The founders were American and Canadian expats Chris Stander, Dan Holman, Martin Neal, Brad Kirkpatrick, Morgan Sowden, Ron Barack, Charles Kane, and Ken Ganfield.

“We really wanted to build a business with the Americans and the Canadians, we liked each other,” Saša recalls. However, the Terminal team asked the duo to hold on while they negotiated an acquisition with Telenor. It was 1998 already, and Telenor was rapidly expanding its Internet operations in Eastern Europe via its Nextra fixed and mobile Internet division.

Why Prague?

In the late 1990s, Telenor (Norway’s state-owned telecom operator) had ambitious plans for expansion into Europe. The plan was to create a federation of ISPs from almost every European country, then use that synergy to leverage data traffic, VoIP, and other IP services, which started mushrooming right around at that time. Telenor was looking for a “beachhead” to park their drakkars and launch that expansion, and to act as a testbed for new approaches in management and service provisioning.

Telenor chose the Czech Republic as its target country because of the location, population size, and a fairly high level of technology development combined with a relatively low cost for skilled workers. Then, within Czechia, they looked to acquire a company with the most “Western” operating principles and corporate culture. It turned out to be the Terminal Bar.

After Telenor acquired several other Czech ISPs to boost its presence, Captain and Saša became its independent contractors. Their Eastern European voicemail IP wonder app was a perfect fit into the larger scale of Telenor’s corporate strategy. They started expanding their team… which leads us to our next hero.

From Valhalla and Astral to Nextra and Telenor

“I love that feeling when you realize how various and sometimes unconnected pieces of technology, people, and design patterns click together like a puzzle to form a solution to a problem or a better way of doing things. This is what I do all the time, applying it to a range of problems: from mundane everyday things to the global challenge of enabling telcos to catch up on technology adoption,” says Andriy Zhylenko, co-founder and CEO of PortaOne.

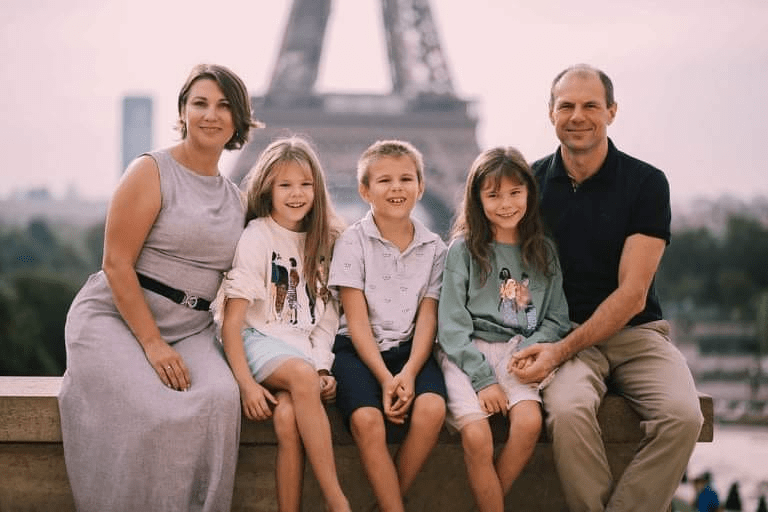

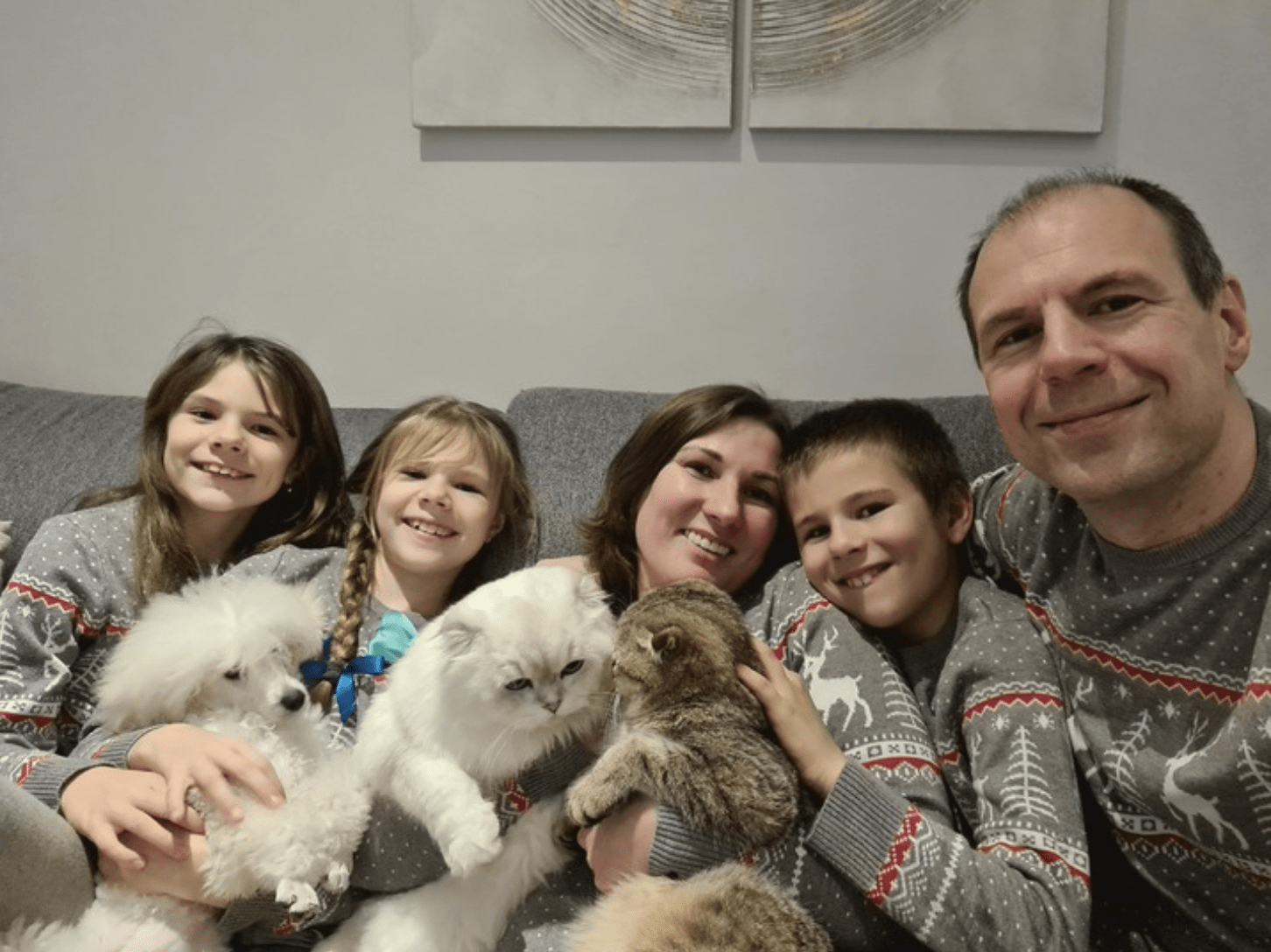

We are in the middle of a TDI via Slack for Android. Andriy is also walking his dog in a playground near San-Sebastian Beach, his three kids playing nearby, while his wife is doing the Saturday shopping. It’s a traditional “Saturday sync” call. He prefers doing “all things content” on Saturdays, because that’s when his mind “is free from the daily routines.” Nevertheless, he admits occasionally checking the commits to the code repository while on the call: “Don’t worry, that’s automatic, my full attention is with you.”

The Slack connection goes wonky. Either Andriy’s LTE has coverage gaps or, despite $1.4B in funding, the SF-based “not a startup anymore” is greedy to buy regional content delivery clusters to bring Kyiv and Barcelona ping-closer. “Ok, I know you are a millennial, but can you call me from PortaPhone via our internal PBX, running PortaSwitch? It uses SIP or falls back to connecting via GSM. There will be no interruptions and I want to quick-test the connection in this environment. We’ll do a Zoom screen-share in 20 minutes, when I arrive home and to my laptop,” he offers.

Ukr.Nodes

“It was 1994, I was a third-year student at Kyiv Poly and I was working as part of a newly established software development team in Astral-Kiev; we were writing an ERP for Kretz Technik, an Austrian company manufacturing ultrasound medical equipment,” Andriy says. “We had an early version of ‘agile development’: every evening we would compile an updated version of the application and send it to the customer. We only had a dial-up connection using V.32 modem at 9600 bit/s (phone line and the weather permitting) – no websites, no file download, no YouTube! And the maximum email size our ISP allowed back then was 64 kB, while we needed to send megabytes of data overnight. That was huge.”

So he wrote an app that split the compiled program into hundreds of 64 kB emails. He would hit “send” and leave the modem working the whole night. He also wrote a program that Kretz could use to extract and assemble the program upon receipt. “That was long before The Bat! and WinRar had it,” he says.

As traffic volume and the file size increased, Andriy decided they needed a proper “fast” connection. The cost of getting a permanent 128Kbps connection was sky high back then, so Andriy created a business plan for becoming an ISP and supplying connectivity to the tenants of the local business center to recoup costs. To set things up, he learned the principles of routing and managing IP networks and Unix (in particular FreeBSD), and installed the first server (valhalla.astral.kiev.ua) of new Ukrainian ISP Astral.ua, which is still run by Andriy’s former associates today.

Being a sysadmin of a real ISP turned you into a “node” and gave you a ticket to Ukr.Nodes – a newsgroup and gated community for the Ukrainian Internet Illuminati. It survived to our times as a Google group, though at the cost of its former pride and glory.

A Body Shop v. the Norsemen

In the mid-1990s the coding body shops were intensely scavenging Eastern Europe for talent. Their business model was (usually) simple: 1) Lure young programmers with employment visas and a promise of a better life. 2) “Pimp and pump” their CV and English. 3) Find an employer who will cover “the talent search fee.” That’s how the Ukrainian tech lobby populated Greater Seattle, Silicon Valley, and NYC in the early 2000s.

In 1998, Oleg Hrynchuk was a sysadmin in the Terminal Bar. He joined Nextra together with Captain and Saša. Being an active contributor to Ukr.Nodes, Oleg referred Andriy to Brad Kirkpatrick (one of the Terminal Bar founders) for an interview, and soon enough Andriy received an offer to become a lead software developer at Nextra. He would take care of the home-developed billing system and merge it into the Norwegian system. The legacy system had been developed by a succession of multiple people. The result was layers of radically different programming approaches and code styles. Even the language of the comments changed based on which “era” they related to, going from German to English and then Czech.

Here was the problem: Andriy had passed the interviews and accepted an offer from a body shop to move to the States almost a year earlier. His work visa package arrived via FedEx only three days after Andriy got the offer to join Nextra. “Back then I loved two things in life the most: telecommunications and Nordic mythology and culture,” Andriy recalls. Obviously, a body shop stood no chance against Telenor in this case. Right after his 24th birthday, Andriy set off to Prague.

On Václavák Alone

Arrival to the Telenor world wasn’t in business class with five stars hotels. “I traveled from Kyiv to Uzhhorod by an overnight train. Then I took a two-hour shuttle to Košice, Slovakia. The driver played the worst pop music I ever encountered in my life.” Then, a train from Košice to Prague. And if that wasn’t enough to test Andriy’s determination to work for Telenor, then came the next surprise.

At that time, Nextra was hiring people all around Eastern Europe. Teams and businesses grew fast. Housing all of them required a bigger office. So Nextra moved all the administrative divisions (including HR) to a new location. Andriy’s train from Košice arrived late Friday evening. He was supposed to pick up his apartment keys and the papers at the main office reception.

But Andriy only had the address for Telenor’s old office, which was dark and closed when he arrived. Fortunately, during the chit-chat of various phone interviews, someone had mentioned that the new office was going to be on Václavské náměstí (St. Wenceslas Square) right above the Bata shoes store – and fortunately, Andriy remembered that detail.

With a backpack on his shoulders, he wandered through an unfamiliar city, looking for the Bata sign and wondering whether anybody would be there at 9pm on a Friday. At that time, he did not speak Czech.

The Good Samaritan

Luckily for Andriy (and for PortaOne), one person was there, pulling an all-nighter. Happy to give his eyes some rest, he opened the door for this stranger with a backpack, who had a face and clothes that felt familiar to home. That person was Saša Starovoitov.

“Innovators” v. “Conservatives”

Scandinavians are good at long-term investing. This, in turn, requires a good money-counting culture and transparent reporting. Of all the regions in the world, Eastern Europe is, probably, the closest to an exact opposite. That’s why Telenor was determined to implement a unified billing system in the region.

But unifying the zoo of home-made billing solutions required a lot of patience and effort. And with each new ISP acquired, that zoo got yet another resident system.

There were two schools of thought within the Nextra division at that time. The “innovators” advocated hiring local teams of entrepreneurs and ultimately buying the one with the best solution. The “conservatives” preferred in-house development, using Telenor’s own Lisp-based billing system, which was named K2. According to our sources, K2 is still running in production as of 2021!

How Did the Dotcom Crash Help Launch PortaOne?

Captain cooperated with Telenor in the VoIP direction. However, he was aware of the “innovators” and decided to build an MVP on his own in 1997. He recalls: “Sometimes people would ask why we spent their money so slowly. It was crazy. We worked in the office during the day, then we would go home and continue moonlighting until the early morning.”

Then, all of a sudden, it was 2001, and people stopped talking about “burning faster.” Telenor shifted its focus from the pan-European ISP network to a mobile carriers business. Obviously, the “conservative approach” to ISP billing got the upper hand. Captain, though, disagreed – he decided to continue developing “the billing MVP” on his own. This coincided with huge life changes for all three of our founders: Captain immigrated to Canada with his family. Alexandre Starovoitov met his future wife, Staša, and moved to Ljubljana, Slovenia. And Andriy Zhylenko also married and ultimately decided to give the United States a try. He opened a map, looked for the closest big city to Vancouver, Canada – and so ended up in Seattle.

Never Accept a “Failure” Without Challenging It

Now it’s time to introduce Kostyantyn Deribin, our fourth hero. Remember the testing environment emulating the Soviet Central Office Exchange? That was a joint course paper. Kostyantyn focused on hardware, while Captain experimented with the firmware. “We went on to the graduation exam as a team; they allowed teaming for engineering majors,” recalls Kostyantyn.

At first, it seemed like their team had failed the graduation exam task. But then, they proved that the task itself was wrong: “It was impossible to create the system our professors described. There was almost a riot after other student groups discovered what we had figured out. Those groups before us had just quietly accepted ‘failing’ without any objection or doubt,” says Kostyantyn.

In 1998, years after that victory, Captain had invited his university pal to work in Prague. Kostyantyn did a frontend for the “billing MVP,” which by then had the brand name DebiTel. (They derived it from “debit cards” and “telephony”.) Tired of “herding cats” (trying to make very different engineering teams of various Nextra branches to adopt and follow common strategy) Andriy switched sides, from the “conservatives” camp into… well, let’s call it “the unknown.” Yes, sometimes you switch sides even from Manowar to Idina Menzel, especially when you are a father of three young fans.

DebiTel and Working from Home Before It Was Cool

“By summer 2002 everybody was in a different country,” recalls Kostyantyn. “I stayed in Prague. Time zones were a total hell.” There was no GitHub in the early 2000s, so Captain installed an SVN server in his Vancouver home. He and Andriy (crashing on a couch in Captain’s guest room) coded when it was late night in Prague, then Kostyantyn woke up and coded his part, while “the other side of the Atlantic” was asleep. Saša (already based in Ljubljana) drew the interfaces and ran the website.

The team conducted regular online sync-ups, which they ran via ICQ and various VoIP clients. Often, everyone was awake at once, regardless of time zones.

Porta Software and Rebranding to PortaBilling100

DebiTel was a great brand name. While it lasted. At some point, the “founding fathers” discovered a major telco operating in Germany under the same brand. 😂 But no matter: the team had already caught on to the idea of starting from a clean slate. They wanted to re-develop the billing system from scratch so the new architecture would not be tied to any specific service (such as prepaid calling cards), and would allow a telco to invent a totally new service and charge for it without modification of the program code. So the company was renamed to reflect this radical transformation.

Jump forward 20 years: it worked. Our system has evolved around that same core, which the founding team developed in 2001–2002. Businesses are now using it to manage and charge for a variety of services, starting from “typical” telco such as hosted IP PBX or MVNO and going to “exotic” ones such as an IoT service for the “virtual bottle” of Johnnie Walker in Brazil or enabling Dutch emergency workers to work remotely during the lockdown.

In 2001 Captain incorporated Porta Software in Vancouver, British Columbia. Canadian laws at that time required a company to have its “business activity type” in the corporate name to be included in the register. Portals were quite popular at that time, but “Portal Software” was already taken. “So we decided to go with Porta, like ‘door’ in Italian,” says Captain.

Origin of the PortaOne Brand Name

The partners renamed DebiTel into PortaBilling, using the “Porta” prefix and adding 100 to underscore the sense of maturity (i.e., “we’ve been doing this for some time”). According to Andriy: “The ‘one hundred’ number also meant that one instance of PortaBilling could process 100 simultaneous call attempts per second. This translates to roughly 15,000 simultaneous calls, the entire calling capacity for a city with 30 to 50,000 people. We were particularly proud of that.”

Using numbers in branding was particularly popular in the 2000s, with brands like Forever 21, Six Flags, First Data, Century 21, 3M and 23andMe. Captain recalls: “Saša came up with PortaOne. We liked to be ‘the one.’ It also had a connotation with music equipment from the 1980s, which reminded us of how we met at Kyiv Poly.”

Ramping up Sales

By 2004, PortaOne was maturing. The developer team had grown and there was less need for all-nighters. The “Prague startup” was ferrying well. Clients started appearing all over the world and the team discovered they needed somebody to lead sales and business development on a larger scale. That’s when Captain remembered a colleague from Telenor named Roman Khalenkov.

“My wife wanted to move out of Moscow to Europe. She got an offer in Prague at the office of the multinational corporation she was working for at that time. Still, her Russian bosses wouldn’t let her move to a different office,” explains Roman via Zoom as he sits on a sofa in his Barcelona home. “So we went va banque and moved anyway. Sometimes you just follow your soulmate for no reason other than… well, she’s your soulmate. I didn’t know the Czech language and had virtually zero business contacts in Prague. After we moved, I started anew: going around, meeting people, telling my story and explaining that I need a job.”

Soulmates and the Prague Adventure

Moving to Prague was a gamble. Roman quit his well-paid job at the Moscow office of PwC. Earlier, he had graduated from the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN), dubbed the “Cold War Harvard” for its role as the model Soviet and then Russian educational institution for foreigners. “I know very few Russians could get into RUDN at that time. Still, I tried and they accepted me.”

After graduation from RUDN, Roman went on to study business administration and finance at Calvin University in Michigan. Having a US degree back in the early 1990s could get you a job anywhere in Moscow. So being an unemployed jobseeker in Prague totally contrasted Roman’s previous lifestyle.

“At some point I stumbled on the Terminal Bar and met with Brad Kirkpatrick and his team. I also met Captain and Saša there. Right at that time Telenor acquired the Terminal Bar and Brad became Nextra’s head of business development in the Czech Republic. He offered me the position of PM and then I became his deputy. After Brad died, I carried on as the Head of BD. Captain and Saša were part of my team.”

After Nextra, Roman moved with his family to Canada, just like Captain. But instead of Vancouver, he settled east, in Toronto. “Roman can talk anyone into anything,” Captain says wryly. “So when we felt our sales needed a boost, I contacted him and offered the position of sales director.”

The Travelling Band

Roman started splitting his time between Canada and Russia, where he had a foreign investment consulting business. “It was financially rewarding, but at some point I got tired of spending most of my time on a plane from home to Moscow and back,” he recalls. So he gladly accepted a position that would require less traveling. Or so he thought it would.

With successful showings at international trade shows like CeBIT, CES, and MWC through the 1990s and 2010s, PortaOne’s business model started to take shape. “We opened technology offices in Ukraine, Vancouver, and, after the EU tightened its data privacy requirements, Barcelona. Roman and the team would travel to various trade shows and meet prospects, while the technology and support offices in Ukraine provided customer support, engineering follow-ups, and built new features according to customers’ specs,” explains Andriy.

The Distributed Team

Practicing what they preach, PortaOne started hiring more remote professionals all across the globe to help with sales, customer support, customer success, technology architecture, and more. Everyone could communicate using the company’s own product: PortaSwitch for remote IP telephony, with a blend of online collaboration tools. Thankfully, such tools started to appear and proliferate right at that time. Think Google Docs/Workspace, Confluence, Roundcube, Slack, Zoom, and many others.

Each of the founders understood these tools perfectly, because they had been among the core users of this technology stack since the times of using ICQ chat and an SVN server in Captain’s Vancouver apartment. “We still don’t have ‘the head office,’ because there is none. Only the one we need for regulatory and compliance reasons,” explains Oleksandr Kapitanenko.

The Epilogue

Kostyantyn

Ironically, of the entire “Prague Five,” only Kostyantyn Deribin, the very last one of PortaOne founders to arrive there, still resides in Prague as of 2021. In 2010 he left PortaOne to join GoodData, another great Czech startup that works with big data analytics. “I love early stage startup culture. So with GoodData in 2011 it was very similar to PortaOne in 2001. It was a great feeling with all that uncertainty and all-nighters, then they got to the venture round. Things became corporate-shmorporate. So I felt that was time for me to move on.”

Now, Kostyantyn is an active contributor to the 3D modeling, molding, and printing community. “My first experience with Blender occurred in 1998. The software and hardware changed dramatically since then. Now I’m finally having some rest from of all those startups and all-nighters. And it’s fun to play with Blender and my own private meteorology station.”( Kostyantyn sent me the link to his pet project, but added a caution: “Please, under no circumstances share the link in your blog. The station is hosted on my home network and I don’t need any DDoS or other types of unnecessary attention.”)

Saša

Alexandre Starovoitov lives in Ljubljana with his family. He is co-owner of the Prulček live music venue, which a top-rated Tripadvisor review called “a place unique to Ljubljana.” Before the lockdown, Prulček hosted several hundred concerts a year, mostly but not limited to jazz jams. Besides occasionally playing at his club, Saša frequently experiments with other types of art, including digital visualizations and photography.

Saša still contributes to daily operations at PortaOne as head of design, including making the cover image for this blog story. His upcoming challenge is redesigning portaone.com. “After all, corporate websites should get a redesign, you know. Once in a decade is enough,” he says.

Roman

The corporate joke goes that Roman Khalenkov liked MWC so much he decided to move to its host city Barcelona in 2014. Andriy Zhylenko followed with his family in 2019, making Barcelona a sales and technology cluster for PortaOne. COVID and the lockdown finally “landed” Roman at home, where he continues to lead PortaOne sales while enjoying more time with his son.

“Somewhere around 2018, I started having this feeling that we should limit our events. The way people buy in B2B was changing dramatically. Now, in the midst of a lockdown, it’s evident that the age of trade shows is gone. What comes next and how we should adapt to it – frankly, I’m still figuring that out,” he says. Nevertheless, 1Q2021 was one of the best sales quarters for PortaOne so far. “People are now buying in a different manner, but they’re still buying, a lot. Remember: it’s telecommunications and remote work, which are the backbone for the current global work-from-home economy.”

Andriy

“I mastered the art of online job interviewing so people don’t have to take overnight trains and buses,” jokes Andriy Zhylenko. Hiring and managing talent is now a crucial part of his daily curriculum at PortaOne. Before the lockdown, he split his time between Spain and Ukraine, where his parents still live, and where PortaOne does most of its product development. Then Spain went on a strict lockdown, so for now the time splitting occurs only online.

“In 2001 we were lucky with the product and market fit. PortaOne appeared in the right place and the right time. Now, when all of telecom is disrupted by OTT players, business models like SIP trunking, MVNO, or IP Centrex will have to adapt and face this new reality,” he says. “I’m optimistic because we had switched our core to containers and WebRTC. But the real power of our platform comes from its openness, which gives operators the ability to innovate in-house. Sometimes it’s fighting the ‘big guys’ back with a solution that better addresses the needs of a specific customer segment. Sometimes it is turning your enemy into an ally, such as reselling integrated Microsoft Teams subscriptions as a part of a hosted PBX service. These are going to be in a high demand for the nearest decade,” reckons Andriy. It’s clear that the old guns are still kicking.

Captain

“Let’s finally finish this blog story and move on. I have so many things in life to do. Dictating memoirs over Slack is not one of them.”

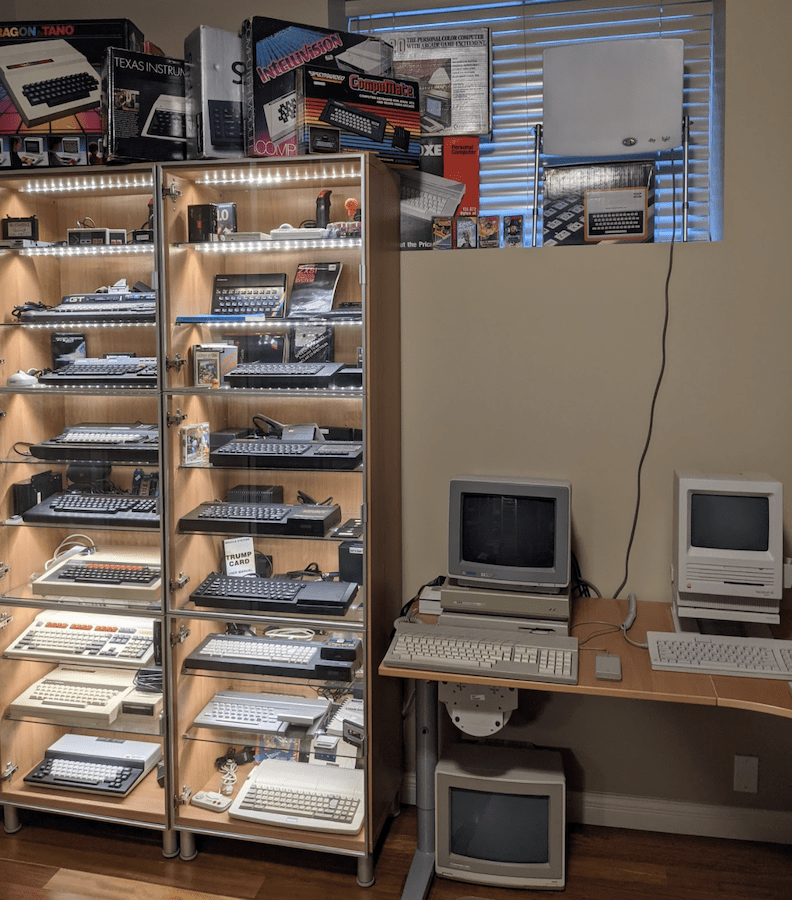

Captain’s current “next big thing” is the DREM (or “Drive emulator”) – a hardware solution for systems equipped with MFM/RLL HDD and floppy drives (take that, Elon). As the DREM website tells visitors: “We feel your pain when these treasured but time-worn mechanisms break down because it is impossible these days to replace them.” Captain says he needed the MFM/RLL solution for his computer collection. Then he (obviously) tried selling it. Exotic as it may look and sound, DREM quickly found its market and sold in hundreds. Customers include the US Army, semiconductor manufacturers, paper manufacturers, sound recording studios (Airstudios, London), musicians, and computer collectors.