Our customers discuss PortaOne Support. The sales department brags about PortaOne Support. Our competitors value the quality and professionalism of PortaOne Support and PortaCare. Yet there wasn’t a single blog story about these smart, insightful, and heroic people. We are addressing that lapse right now.

Inception: Our Founders Were the PortaOne Support Team

“It’s hilarious to recall now, but it wasn’t fun back in 2002,” laughs Andriy Zhylenko, who invented names and registered email accounts for a whole team of fictional PortaOne support engineers to create the impression that PortaOne was not just a start-up, but a “real corporation” with a “large team of support engineers.” The reality: initially, that large team was just Andriy and Kostyantyn, sometimes aided by the Captain and other founders.

Ironically, the trend is the opposite in 2023 — today, each PortaOne support engineer (currently around 100 people) uses various software tools for their digital workspace. Many of these are commercial software that requires a license. In rough times like now, one’s “economy has to be economical [efficient],” as a long-time Ukrainian saying goes. Therefore, we now limit the number of workplace licenses/subscriptions (hello, chatGPT+), hence the number of workspaces.

PortaCare Gets Its First (Real) Support Engineers

By 2003, PortaOne had gathered a sufficient enough customer base to consider creating a simple customer support service. However, in the early 2000s, making such a service required an actual office. Decentralized online support run by remote employees and digital nomads still had yet to come into existence (thank you, lockdown).

“Kyiv was an obvious location of choice,” explains Andriy Zhylenko. Despite being spread all across the globe by the early 2000s, most of our PortaOne founders grew up in Kyiv and had a vast network of personal and professional connections there.

Last but not least, in 2003, Ukraine was offering a much more competitive workforce (based on salary/actual deliverables ratio) than the EU, North America, Southeast Asia, or Australia/Oceania.

“The Brother of True Metal”

Historically, Kostyantyn Zhylenko was the first Head of support at PortaOne. “No, we’re not related,” says Andriy Zhylenko when discussing Kostyantyn’s role in the early years of PortaOne Support. However, there’s a funny story that mixes the early Internet days, Manowar fandom, and the usual human curiosity.

“I was using a BBS,” Andriy recalls. This was long before identity theft became a widely known (and feared) concept. All of a sudden, the admin started attacking Andriy with pointed questions: “who are you?” “what are you doing here?” and, finally, “is your last name really Zhylenko?” That’s when Andriy was able to clear things up (to his relief). Turns out, attention was drawn to having the same last name, plus the choice of “manowar” as a username. (Manowar is a popular heavy metal band from the US.)

Luckily for both Andriy and Kostyantyn, PortaOne was looking for an experienced IT professional to lead its customer support. And that’s how a random acquaintance ended up with a new job, and that’s what led to the birth of a new function for PortaOne. To make things even more complicated for our customers and employees, the duo preferred to address each other as their “Brother [of True Metal]” — that’s how the band Manowar addresses its fans. Kostyantyn successfully led PortaOne Support from 2003 to 2006, when he moved into the position of a senior applications engineer. He had learned that he preferred true engineering (like true metal) to the more “political” management roles.

The Era of Oleh Kostyuchenko

Back then, it was normal for large Ukrainian IT companies to work from rented apartments. Commercial real estate was scarce and often (unjustly) expensive. It also “scared away” the IT folks, who back then were mostly the “home-sitting types,” explains Oleh Kostyuchenko, who became leader of PortaOne Support after Kostyantyn Zhylenko. Almost two decades later, Oleh is still with PortaOne, working as our part-time contractor/evangelist in Canada.

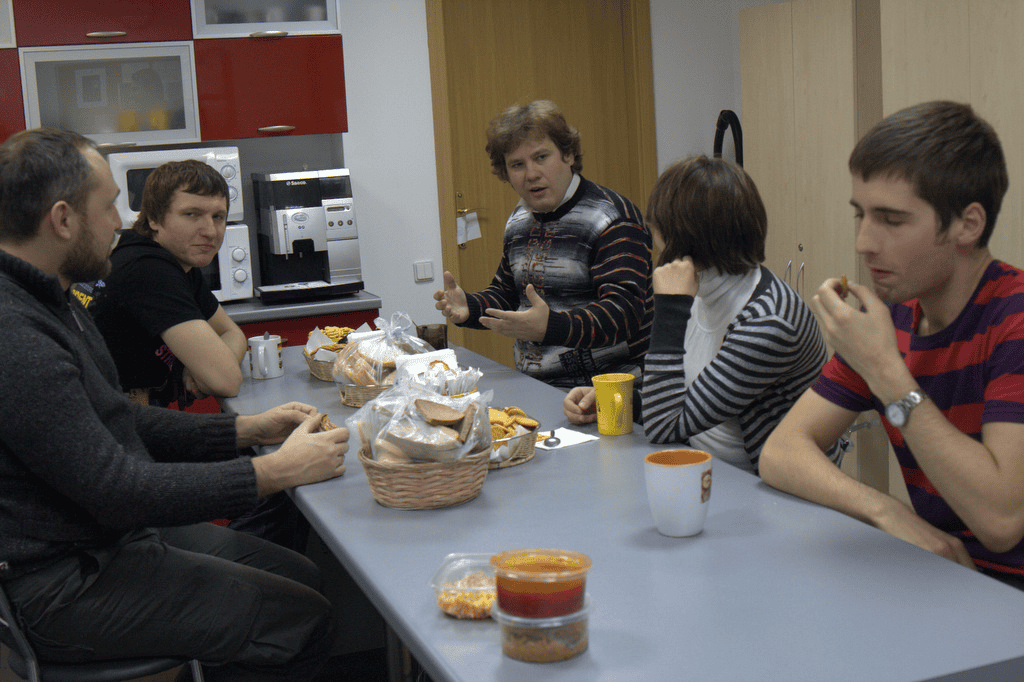

The (Apartment) Kitchen Mentality

What people in the US today call the “garage mentality” was called the “apartment kitchen mentality” back in Ukraine in the early 2000s. “We rented several apartments in good and quiet neighborhoods of Kyiv,” explains Andriy Zhylenko. There were originally two apartments: one for developers and one for support engineers. This separation wasn’t intentional.

The typical Soviet-style residential building of 5, 9, or 16 floors has apartments of up to three bedrooms, plus one kitchen, one restroom, and a tiny “hall” or welcome area. Therefore, the number of employees one apartment could comfortably host was usually 6-8 people. By 2003, PortaOne had over a dozen employees. That’s why this crowd needed two flats.

Catering wasn’t very popular in Ukraine back then. So the usual way to have lunch (and dinner) was to go to a local doner place. If you did that often, your digestive system would not last long. Therefore, a more viable alternative was to cook using the apartment’s kitchen. That’s how a tiny post-Soviet kitchen became the meeting hub to discuss and crash-test new ideas. Many (now legendary) Ukrainian startups began in a similar way, including Viewdle, Grammarly, and MacPaw.

“Cooler Talks” Were “Balcony Talks” and “Team Building” Was an Airsoft Tournament

“We hadn’t met ‘the dudes from that other apartment’ for months,” recalls Dmytro Manshilin, another PortaOne early-timer who is still with the company (for over 18 years now). “They were doing their job, and we were doing ours. Why change something that works?” The “offices” were located in different neighborhoods of Kyiv. Besides the kitchen, the usual place for discussions (of current events, TV shows, etc.) was “the balcony,” which in post-Soviet-Ukrainian architectural gratte-ciel is a street-looking terrace usually covered with a patchwork of different-looking (and awkward-looking) glass windows (the notorious “sklopaket”). You smoked or had coffee/tea, watched the pedestrians and cars passing by, and “talked about life.”

The early PortaOne Support team also credits Oleh Kostyuchenko with one of the earliest team-building events (where the two “offices” finally actually “met,” not just played the first-person shooting games online). “It was the summer of 2005 when I fell in love with a new hobby — airsoft,” Oleh recalls. Corporate summer events [“the korporatives”] were becoming particularly popular back then. So Oleh offered to organize an event where employees could spend time and hang out.

“Our generation grew up playing computer games, particularly first-person shooters (such as Duke Nukem, Doom, Quake, and Half-Life). Therefore, all of the engineers were happy to “play Doom for real.” That was long before “Doom for real” became the sad daily reality for Ukraine and for many of those happy airsoft players of the mid-2000s.

How Did Ukrainian Airlines Influence the Early Ramping Up of PortaOne Support?

Besides team building, Mr. Kostyuchenko was also instrumental in transforming PortaOne Support from its “kitchen mentality” (which was perfect for its time) into a “grownup corporate” one. In the early 2000s, few Ukrainian customer service professionals spoke English and (more importantly) understood the cultural difference between “Soviet customer service” and real customer service.

Luckily, before joining PortaOne, Oleh worked for the Ukrainian Airlines IT department. “It was a great experience. I joined UIA in 1994, right after graduating from the university. It wasn’t my first IT job. However, it was a job like no other. I traveled worldwide to maintain and support their IT systems.”

The “Service” Tickets

“We had ‘service tickets’ (the real airline tickets, not Jira, Trac, or whatever). With it, you could fly anywhere worldwide, not necessarily using your airline,” Oleh recalls. “Our main customer base was foreigners and international travelers. That exposed me to a different world than home and apartment kitchens.”

So when Oleh joined PortOne in 2004, his previous professional experience had quickly earned him a C-level position. “We had to implement formalities and procedures. Although everyone admitted it was fun, the ‘kitchen era’ was over. It may sound boring, yet as an outcome, PortaOne Support became a modern international customer service, ready to serve customers from all over the world,” explains Oleh. In 2008, he left PortaOne to become CIO of Ciklum, the large Ukrainian-Dutch IT outsourcing company, then immigrated to Canada in the mid-2010s and rejoined PortaOne as our contractor.

Introducing Escalation Levels, PortaOne Support Groups, and Software Versioning (Before the “MRs”)

After UIA and before PortaOne, Oleh worked for ISS (now called REATISS, so not the International Space Station). It’s a Ukrainian subcontractor of Motorola, Freescale, and others, specializing in reverse engineering and industrial intelligence. “While UIA offered great international exposure, people at ISS coached me in building systematic and lasting teams for specific tech functions,” Oleh explains.

Oleh used the expertise he gained while working for ISS to introduce escalation levels at PortaOne Support and to launch our release versioning. The latter happened before the PortaOne Agile team introduced “the MR” versioning in 2011. However, the groups on which PortaOne Support still relies almost two decades afterward were the breakthrough indeed.

The support groups first appeared during the Kostyantyn Zhylenko Era. Several years afterward they acquired a new meaning under the supervision of Oleh Kostyuchenko. “As the number of support engineers grew, I noticed that some of them preferred working with certain technologies and customers, building niche competence,” Oleh recalls. The customers were also happy to work with the same people repeatedly. This helped build lasting relationships. Since 2005, PortaOne has introduced over ten various support groups. Our next blog post in the PortaOne Support saga will cover their composition, structure, and functions.

Launching Our PortaOne Support Call Center, Customer Success Managers, and Day-to-Day English Classes

In 2006, PortaOne ultimately got an entire floor in an office building in Kyiv, close to the Boryspilska municipal metro (subway) station. Ironically, in 2009, UIA also relocated its main office there.

“It wasn’t downtown, but it was an entire floor! Getting most of our Ukrainian team literally ‘at the same level’ opened opportunities for functional growth,” recalls Andriy Zhylenko. PortaOne Support became the “talent incubator” for the project management office and the sales team. (It would sprout up from PortaOne Support as a standalone department several years later.)

The need to support customers worldwide effectively and professionally spurred another department — our Customer Success Managers. We created this team to assist and care for customers on a different level (and to teach our engineers the soft skills). The CSMs deserve a different storyline all on their own. (Which they will get some day soon.)

The “Bobovski Phone Set” and Why It Mattered

In 2006, Ms. Irina Bobovskaya became our PortaOne “proto-CSM.” “We had the “Bobovski phone set,” recalls one of our early employees. It was an actual physical phone, and it was called from time to time. The trick was: Irina lived in Canada, and the phone set was based in Kyiv. We used our PortaSwitch installation to make it a “Vonage style” call. The device had the last name “Bobovskaya” taped over it.

All support engineers dreaded that phone set because “when it called — it meant trouble.” After a complicated technical situation when a communication gap (the engineers honestly thought they should solve the actual problem ASAP and should not distract themselves by sending status updates & etc.) almost resulted in a loss of a customer, the Captain hired Irina to handle crisis communications with customers. She was also responsible for creating the first PortaOne Support call center.

Introducing the PortaOne Support Contact Center

Since the origins of PortaOne, most of our support was asynchronous. We performed it via email, and all communication related to specific issues accumulated as a support ticket in the RT (Request Tracker). Despite over a dozen attempts to replace this system with Zendesk, etc., RT has been functional at PortaOne for over two decades. It was an open-source project, so we extended it with additional tools and widgets to help the support team. However, sometimes a situation requires real-time communication and the attention of PortaOne engineers. That’s how the call center started, and that’s why Irina was given “special authority” for direct interventions on behalf of our customers.

That call to the “Bobovski phone” meant: “Stop doing whatever you are doing now, answer the phone, and solve the situation quickly.” The modern reader should understand we are talking about the mid-2000s here. Social networks had not yet appeared. The usual way for customers to signal trouble was by a phone call or email “to the bosses.” Whenever the sales team, founders, or support engineers smelled anxiety and conflict, they invited Irina to the conversation.

The Woman Behind that Legendary Phone Set

In a Zoom interview almost 20 years afterward, Ms. Bobovskaya (she now prefers the Westernized spelling of her name — Bobovski, pronounced like the well-known Lebowski) does not look scary or dreadful. Instead, she is polite, educated, and full of humor and irony. “The founders invited me to join PortaOne because somebody had to love our customers,” jokes Irina at the beginning of our conversation. That laughter set the tone.

Irina worked remotely from Canada. However, she frequently traveled to Kyiv to meet and greet the new PortaOne Support engineers and developers. “At that time, I was in my early 30s, and most of the Kyiv team were in their early 20s. What struck me is that those dudes literally lived in the office.”

“Several More Hours”

“Once, I approached someone late in the evening to say hi and ask what he was doing,” Irina continues. “To my astonishment, he replied that he was relaxing after a day shift. I asked why he was still at his desk. He said, ‘That’s how I relax: several more hours of browsing the Internet or listening to music on a computer.’ Several more hours of screen time after an exhausting 10-hour shift! This was long before Ukrainian developers started attending SPA and yoga classes ‘to preserve the balance of work/life’ (or is it war/life?).”

After working for PortaOne for five years, Irina Bobovski left to join Langara College (BC, Canada) as an associate registrar. “The impending crisis [of 2008] was looming on the horizon, so while I was happy with my PortaOne adventure and frequent business trips to Ukraine, I felt the need for something stable and state-funded. Working at the state college provided all the above.” Ms. Bobovski is still working as a registrar at Langara at the time of posting.

“Sir, You Have Red Balls” and “Deer Customer”

“We are using our custom-developed app called ‘the Monitor’ to [obviously] monitor all customer installations,” explains Yevhen Petrov, leader of a PortaOne Support team in our Chernihiv office. Based on Nagios, it has red indicators resembling balloons. When everything is okay, the “balloon”… or “ball”… is green. The indicator goes red when something is wrong (e.g., server or service not responding, we detect unusually high load, etc.).

A PortaOne support engineer saw the trouble on his night shift one day and decided to report it to the affected customer. Now, you can imagine what happened when he chose his phrasing. 😂 That moment was the birth of a PortaOne internal meme that is over a decade and a half old by this writing. And it still makes everyone laugh when recalling it. There were similar stories of funny and curious linguistics.

Dmytro Manshilin recalls another email that started with “Deer customer.” Luckily, the customer was located in Canada, so they approached the situation with empathy and joked back with, “Sorry, there are still humans on this side of the line.”

“We Have Been Hardly Working on Your Issue”

However, those “funny linguistics” situations did not always end in laughter. In the late 2000s, the number of our customers was galloping, and the PortaOne Support team was struggling to keep up with the demand. “We faced a dilemma,” explains Andriy Zhylenko. Either you allow more support engineers to communicate with customers directly, and accept that a few “red balls” situations were going to be inevitable. Or, you impose strict customer communication rules and limit direct customer communication only to native speakers or employees familiar enough with the cultural realities of the “First World.” We went with the second option, which, at first, created huge wait lines.

Therefore, when a customer has been waiting for an answer for some time only to receive the reply: “We have been hardly working on your issue” — this might naturally disappoint them. After investing so heavily in our brand and customer awareness, PortaOne now faced the risk of losing those customers we had earned. Rapid growth had fired off an unexpected side effect. It required an immediate reaction. And that reaction arrived with a man named Vlad Chetyrko.

How a Schoolteacher (and Devout Christian) Became Chief Customer Success Officer at PortaOne

“I joined PortaOne on January 9, 2007,” Vlad recalls without hesitation during our Zoom debrief. It was a life-changing event for a schoolteacher with previous professional experience teaching English at a local gymnasium in Cherkasy. Our PortaOne founders have a particular eye for people. Speaking in basketball analogy, Vlad was destined to become the playmaker.

Mastering English for Engineers on a Corporate Scale for Better PortaOne Support

“My primary job initially was ensuring PortaOne Support engineers improved their spoken and written English. However, it quickly became clear that the issue wasn’t grammar or vocabulary. Some engineers wrote and spoke the language with better grammar than some native speakers I knew by then.” However, it was 2007, and the “Ukrainian IT boom,” “work from home/airport/hotel” and the “digital nomads” lifestyle hadn’t started yet. “Engineers were mostly confined to working in the office,” Vlad explains.

Even more interestingly, in 2007, Vlad had never traveled abroad. However, he performed a lot of “virtual traveling” for students at his gymnasium. “I knew that teaching students in a manner like ‘Kyiv is the capital of Ukraine, now please learn these 150 irregular verbs by heart’ is useless,” he says.

Luckily, the gymnasium was no ordinary school. Materials from the US and the United Kingdom were incorporated into the program. Vlad also relied on Microsoft Encarta for visuals and multimedia demonstrations. More importantly, he encouraged experimentation. “The aim was to ensure that students could communicate,” he explains. Vlad started using the same teaching approaches (and practicing empathy) with our PortaOne Support engineers.

Vlad Chetyrko Becomes the CSM Lead

After he spent some time teaching English to all the Ukrainian employees of PortaOne, the founders invited Vlad to join the company to do actual business. “First, I became an account manager in August 2008. However, with time the account manager role morphed towards the sales department, where it really belongs,” Vlad explains.

Since 2008 CSMs have become the final escalation point for our customers. That’s the “I want to talk to your manager” situation. “However, we are purposefully lazy ‘managers.’ We do all we can to prevent ourselves from doing the escalation part of our job by proactively ensuring there is seldom any need to escalate,” explains Mr. Chetyrko.

The Evolution of the CSM Function (Worldwide and within PortaOne Support)

Customer success management appeared in the late 1990s. However, it became spotlighted with the growth of CRM solutions (hello, Salesforce, Hubspot, and others). CSMs are particularly helpful in businesses with high customer acquisition costs, (potentially) very long customer journeys, and enormous customer lifetime value. That’s “hello, telecom” and “hello, PortaOne customer base” situation, with ⅔ of our customers being with us for over five years.

Mr. Chetyrko attributes a substantial share of his professional success as a CSM to experience with being an interpreter on Christian missions to Ukraine. “My service for the Ukrainian Christian community helped me earn a multicultural perspective and provided me with a platform for nonviolent communication and conflict resolution — the skill that’s in high demand for my role as the CSM leader at PortaOne.”

The Next Episodes of the PortaOne Support Saga Are Coming Soon! Stay Tuned

That is all for today. However, this was just the beginning of the PortaOne support saga. Stay tuned for the next story, in which we explain what PortaCare is and how PortaOne expanded our support groups via three different cities in Ukraine: Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy. We will also cover the nuances of working all across the planet (meaning: all 24 time zones), and compare how PortaCare differs from the per-hour support. Meanwhile, please have a pleasant rest of your summer.